Sports

Precision Pistol – Shooting For Greatness

Precision Pistol shooters are phenomenal at focus…it’s quite a feat to be able to consistently nail an eight-inch wide target from 50 yards. JerseyMan sent me to cover the annual State Outdoor Pistol Championship for the December 2015 issue. I learned some amazing stuff. You can view the PDF of the magazine article here.

New Jersey’s top marksmen, shooting for nothing but excellence.

Precision Pistol Shooting For Greatness

“It’s the ultimate badass sport with pistols.”

At the end of “Rocky III”, Apollo Creed challenges Rocky to a rubber match between the two of them…to settle the score of who is the best, once and for all. As Apollo explains to Rocky, it’s only to prove it to himself…“no TV, no newspapers, just you and me.”

Because in the end, that is all that matters to a true competitor, at any level. Self-respect.

Rich Kang, a surgeon from Maryland, has had his picture added to the New Jersey Pistol website, as the Winner of the 2015 State Outdoor Pistol Championship. His name is now engraved on the Madore Trophy.

And that’s pretty much the extent of his recognition for this exceptionally difficult achievement. The top result of a Google search for “Rich Kang” is the LinkedIn profile of a California product developer with the same name.

Precision Pistol excellence isn’t something one pursues for stardom, applause or financial gain. There wasn’t much in the way of an audience or media…other than a lanky, curious writer for a popular men’s magazine…present at the championship event. Shooter Frank Greco likens it to golf: it may not be the most exciting spectator sport, but among participants, there is an unwavering admiration for the best.

“It’s the ultimate badass sport with pistols. In the shooting world, badass is snipers,” he says. “In the pistol world it’s precision shooters.”

Greco is the Regional Vice President of New Jersey Rifle & Pistol Clubs, based in Highland Lakes. A portion of this event took place at the Central Jersey Rifle & Pistol Club in Jackson. Greco didn’t participate in the competition, but he was there to explain the mystique of it, right down to the effect of donut consumption on shooters. True.

“The sugar raises the blood pressure and affects the steady hand,” Greco says, while offering a donut to this observer. “Sugar and caffeine in excess can be Kryptonite to a shooter.”

It’s that demanding?

To say the least.

Could you hit it from half a football field away?

Picture how far 50 yards is. 150 feet. Half of a football field. Now fathom being able to steadily aim and fire a pistol from that distance and consistently hit a target eight inches wide.

That’s just for an eight-point shot. For a 10-pointer, that target is just three inches wide; for a bull’s eye…which is used as a tiebreaker if two shooters have the same score…it is just an inch and a half.

Can that even be done with normal human vision? Yes, and the shooters on the firing line this day are proving it. With multiple types of firearms and various types of shooting…moving targets, rapid fire, timed firing.

It’s a three-gun match, with .22, centerfire and .45 caliber pistols. With each type of pistol, a shooter takes 90 shots. Those 90 shots are broken down into four matches: Slow Fire is two strings of ten shots each over ten minutes; National Match Course is ten Slow Fire shots, followed by two strings of five shots each at 25 yards; Rapid Fire is two strings of five shots each over ten seconds; and the Timed Fire Match is four strings of five rounds each, with 20 seconds per string.

All day long, the barrage goes on. Casings litter the ground. Wisps of dust float from the dune behind the targets. The unmistakable odor of gunpowder fills the air. Wrists snap back in recoil with larger pistols. The noise is thunderous and deafening at times, but that’s the only aural distraction allowed. No talking or other sounds behind the line. During one match a ringing smartphone is immediately shut off; only in church could that be more embarrassing.

It’s grueling, this full day of shooting. Comfortable footwear is a must.

Frank Greco (left), with Ed Glidden (right), the director of the match.

Between rounds a horn sounds and a red light begins flashing. When the light is flashing, guns must be down, and must remain untouched until the flashing stops.

Ed Glidden, the director of the match, calls out instructions to the shooters, obviously with safety as the top priority. Cease fire, magazines out, make the firing line safe. Empty chamber indicators installed. Check your gun; check your neighbor’s gun. And so on, dozens of times. Glidden’s role looks boring to someone witnessing the action. But needless to say, it’s an essential one.

Part of Glidden’s occupation is training shooters in gun safety, including teaching youngsters in the club’s highly touted junior program. “Individual training,” he says, “is keeping the gun pointed in a safe direction at ALL times and treating every gun as if it were loaded. Constant awareness of the range officers and other shooters, to prevent and/or correct the slightest infraction until safety becomes a habit. Any unsafe practice will result in expulsion from the match and the range.”

The Central Jersey Rifle & Pistol Club people have a reputation for their focus on safe handling of lethal weapons. They are frequently praised for it in online reviews. It is particularly impressive to see younger people on the firing line, some barely in their teens, completely comfortable handling firearms. Partly because of Glidden’s repetitious direction, safety is second nature in this competition.

Besides, with the concentration required at tournaments like this, competitors have more than enough to occupy their minds.

Lateif Dickerson (left), who has forgotten more about self-defense than most of us know. (photo courtesy of Lateif Dickerson)

Watching the shooters it appears as though they are cool as ice, with the focus, the concentration, the steady hand. But as one of the better shooters on the line can tell you, it takes years to develop this composure. And even he still grimaces at the occasional subpar shot.

Lateif Dickerson is the master instructor at the New Jersey Firearms Academy. His resume of other titles is very impressive: Certified Pistol Instructor, Range Safety Officer, Combat Handgunner at the School of Defensive Firearms, the list is long. He’s been training civilians, police and military for 19 years in various weapons usage and self-defense.

Dickerson can tell you a bit about becoming adept enough for this competition. There are three stages, he says…know how, physical conditioning and mental conditioning.

Know how is mastering the fundamentals… like stance, breath control, and recoil management. Stance “should be as comfortable but as stable as possible. Think like a crane; your legs are the outriggers, your arm is the boom.” Breath control is “basically holding long enough so you aren’t moving.” Recoil management is the ability to “consistently recover to the same place when shooting.”

Then there’s the physical conditioning.

“A match can go from 9:00 AM – 4:00 PM, or longer. If you start fatiguing during a match your performance will fail. You must be able to hold the weight of your arm and gun up all day – and steady. Holding steady requires an isometric tension that needs to be developed also.”

But the mental preparation is by far the toughest part.

“The ONLY thing that should exist in your mind is that your sight is where it’s supposed to be as the trigger moves rearward…this is very hard. We all have a lot of noise and distractions, so conditioning your mind to focus is a process. That process is largely the challenge in shooting.”

Frank Greco emphatically agrees, sharing a story of his own self-defeat in the mental aspect of the game.

“When you’re in it, on the line, loading, in the zone, improving your score, it’s incredibly intense and extremely difficult mentally.

“One of my first times I experienced the ‘mental game’ was in the NY State Championship. The match director came over to me and asked me if I knew I was shooting better than most of the Experts and Masters. I said no, and got accidentally sidetracked, thinking I was going to win the match. The lost focus immediately showed; my shots were random and my scores went down.

“It’s vital to maintain a positive outlook and to speak to yourself in positive statements. It’s important to train your subconscious mind and create a positive self-image.”

He pulls out his smartphone and shows this observer a picture of a target, the high-value section of it riddled with bullet holes. Sometimes, he says, he needs to look at it during a match, to remind himself what he’s capable of.

The trophy is just a bonus.

It’s all undeniably worth the effort.

The true reward of Precision Pistol, as Greco relates from his own personal experience, is self-respect…the realization of one’s hidden abilities and the ability to meet the most difficult of challenges. Once a person can hit that one-and-a-half inch bull’s eye from half of a football field away, it’s hard to imagine how monthly bills could faze them.

“Great shooters have an almost Zen-like approach to shooting and how they approach their daily lives, jobs, etc. Since I started, my ability to focus has sharpened dramatically, and it’s positively benefited other areas of my life. The ability to focus on what matters, and disregard unimportant matters, literally frees your mind.

“The benefits are real, and to that extent, shooting has made me a better person.”

Did learning about Precision Pistol shooting make your day a little bit?

I hope so. If it did, I would really appreciate your support.

When you use this link to shop on Amazon, you’ll help subsidize this great website…at no extra charge to you.

Thanks very much…come back soon!

Choosing the right equipment is essential, especially with the cost outlay.

Get Started With Precision Pistol Shooting

If you’d like to try Precision Pistol Shooting, there is a website dedicated to helping you get started, with several informative pieces from top shooters. The site is called “The Encyclopedia of Bullseye Pistol”.

Among the articles is a piece by site owner John Dreyer about essential equipment. There’s a lot to know when laying out the considerable funds for pistols…like whether they are mass-produced or hand built, or the differences between high performance and convertible pistols. Not to mention other necessary equipment, like eye and ear protection, scopes and cleaning supplies. Pistol shooting is not a cheap sport, so spend wisely.

Another piece by Dreyer quotes several Zen philosophies and describes the achievements in pistol shooting in how they relate to such quotes. One example: “A man who has attained mastery of an art reveals it in his every action.” Dreyer compares this to pistol shooting in the sense that once a shooter can sustain an “empty mind”, he can see “underlying principles in everyday life and life in all things”.

Another piece from top shooter Jake Shevlin reveals the “secret” to shooting high scores. It’s the same secret one learns about how to get to Carnegie Hall…practice, practice, practice. The shooter must sacrifice…sacrifice time, money, convenience, and priorities in life to excel at just one thing. Top marksmanship requires a level of commitment unmatched by few endeavors. That, says Shevlin, is the “secret”.

The Encyclopedia of Bullseye Pistol website also features a discussion group, e-mail updates, and links and maps to shooting clubs and ranges.

Try it without ammo until your scores improve.

Multiple Champion Dave Lange on Dry-Firing

Dave Lange’s name appears a lot on the NJ Pistol website. He has won the overall state outdoor championship nine times since its inception in 2001; the only other shooter who has won it more than once is Ron Steinbrecher, who has captured the title just twice. Lange was also the NJ resident champion in 2015, though he lost the overall title to Rich Kang.

Lange is the author of a piece for Shooting Sports USA, linked to the NJ Pistol website, detailing the benefits of dry-firing…firing a weapon without ammunition. With dry-firing, a shooter can focus on weaknesses, like maintaining consistent grip. Lange states in the piece that he practices his dry-firing three times a day, 15 minutes each time.

With dry-firing, a shooter can run a mental program through his mind of executing a successful shot; Lange’s program involves picturing a red dot in the center of the bull’s eye and then picturing the bull’s eye with the bullet hole in the center.

Dry-firing can address any shooter’s specific problem, Lange says. The key is being willing to commit to it until a shooter’s scores improve. Given his success, he’s probably got a point.

Phenomenal for most of us mortals. Nowhere near good enough to be a national Precision Pistol champ. (photo courtesy Frank Greco)

The Best in the Nation

The NJ State Outdoor Pistol Championship, according to Frank Greco, is the 3rd largest of such events in the nation; the national event, known as the “World Series of the Shooting Sports”, takes place in Camp Perry, Ohio, 40 miles east of Toledo. Events have been held there since 1907.

The overall National Pistol champion for 2015 is Keith Sanderson from Colorado Springs. He scored an incredible 2,655 points out of a possible 2,700. Second was Brian Zins with a score of 2,641. Sanderson is an Olympic gold medalist; Zins was the 2007 NJ State Champion.

To put those scores into perspective, do the math: 2,655 divided by 270 shots equals an average shot score of 9.83…so Sanderson’s average shot was almost always in that three-inch range for ten points, with maybe one or two in a hundred falling outside of it for a nine-pointer.

The difference between Sanderson’s and Zins’ score was just 14 50-yard shots out of 270 that covered a five inch range instead of three.

One wonders if Zins thought about having a donut the week before the match.

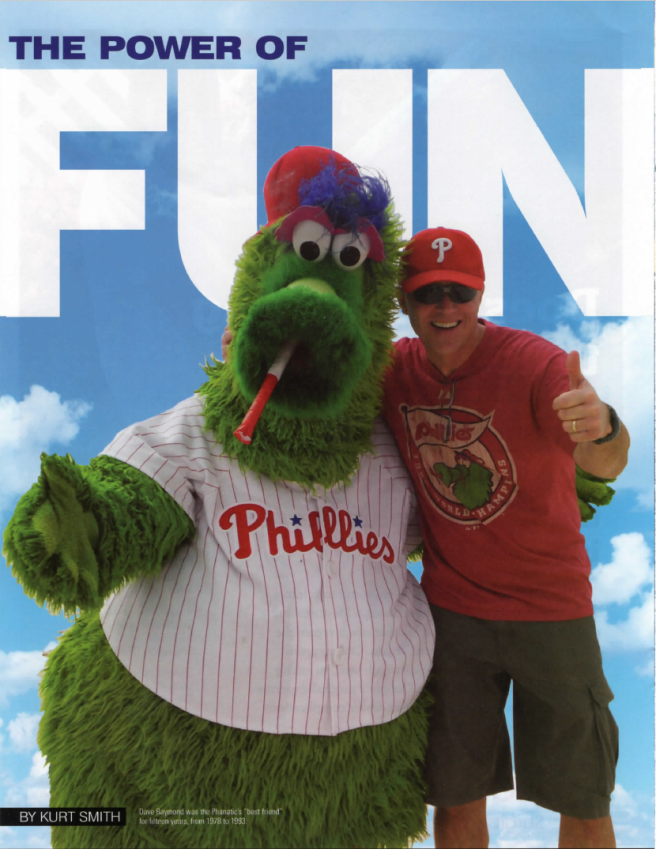

The Power of Fun – Dave Raymond, The Original Phillie Phanatic

The Phillie Phanatic is the greatest mascot in sports…largely because original Phanatic Dave Raymond simply put on the costume, went out and had fun. I had a chance interviewed Dave, who now creates team mascots as the owner of Raymond Entertainment Group, for the April 2015 issue of JerseyMan. You can view the PDF of the magazine article here.

Dave Raymond, the original Phillie Phanatic, with his best friend. (photo courtesy of Dave Raymond)

The Power of Fun

Imagine being a business owner who is looking to improve your marketing. You want a smart, polished, exciting campaign to bring life into your adequate but unmemorable image. You want to target a younger audience that otherwise might not discover your product.

Needless to say, this problem requires professional expertise, so you call in a consultant.

A consultant who, for much of his adult life, made his living wearing a furry green costume, recklessly riding around in an ATV and thrusting his ample hips at sports officials.

Because if your company is a minor league baseball team, and the idea is to bring more kids to the ballpark, and you want to create a mascot on that basis, hiring the original Phillie Phanatic to handle the design is a no-brainer.

As the man behind arguably the most beloved mascot in sports, who today is the “Emperor of Fun” at Raymond Entertainment Group, Dave Raymond understands the marketing value of a fun diversion.

Even if he learned it by accident.

“The joke was that the Phillies got the kid that was stupid enough to say yes,” Raymond says with a laugh. “I was a student at the University of Delaware. I had my fraternity brothers telling me, ‘they’re gonna kill you, they’re gonna hang you in effigy and set you on fire, and that’s when the Phillies win! When they lose you’re really gonna get in trouble!’

“That first day, I went into Bill Giles’s office and said, ‘Mr. Giles, what do you want me to do?’ A smile came across his face and he said, ‘I want you to have fun.’ I was tearing out of his office thinking, ‘Wow, this is going to be easy,’ and he screamed, ‘G-rated fun!’

“The first night I fell over a railing by accident, and people laughed. So I was thinking, I have to fall down more. Slapstick humor was something I loved, I was a Three Stooges fan, I watched all the cartoons. It was Daffy Duck and Foghorn Leghorn and Three Stooges because that’s what they laughed about.”

The Phanatic is also always willing to set an example for fellow fans.

Dancing with the grounds crew quickly caught on, too.

“The first night I did that, I tripped one of the guys by accident, the kid tripped and fell, and people laughed. That turned into me running around the bases and at each base I would knock one of the kids over, and then we would all gather behind home plate and dance. Fans were giving us standing ovations, because they’d never seen the grounds crew animated!”

In a rabid and brutally unsentimental sports town, it also didn’t hurt that the Phanatic could so effectively taunt the opposition. Tommy Lasorda, who could often be described as a cartoon character himself, once even wrote a blog post titled “I Hate The Phillie Phanatic”.

Raymond gets along with Lasorda and has read the post. Their feud was usually friendly, but it could escalate: “One night he just snapped, and he came out and tried to beat the ever-lovin’ you-know-what out of the Phanatic.”

The two smoothed it over, but Raymond retains his proud Philadelphian perspective towards the Dodgers icon. “He’s a wonderful ambassador for baseball; the only problem with him is that he’s a Dodgers fan from Philadelphia. Worst type of traitor we could ever have,” he laughs.

“I understood the psyche of the Philadelphia fan. I was one of them! I hated the Mets, I hated the Yankees, I hated the Celtics. And the Dallas Cowboys, to this day, I see Tony Romo in a commercial about pizza and I run and turn the TV off. I knew the fans would cheer when I stepped on a Mets hat or made fun of the Dodgers. I wanted to do that, because I hated the Dodgers, and I hated the Mets!

“It was that type of thing, and you put all those together and make a cartoon character out of it.”

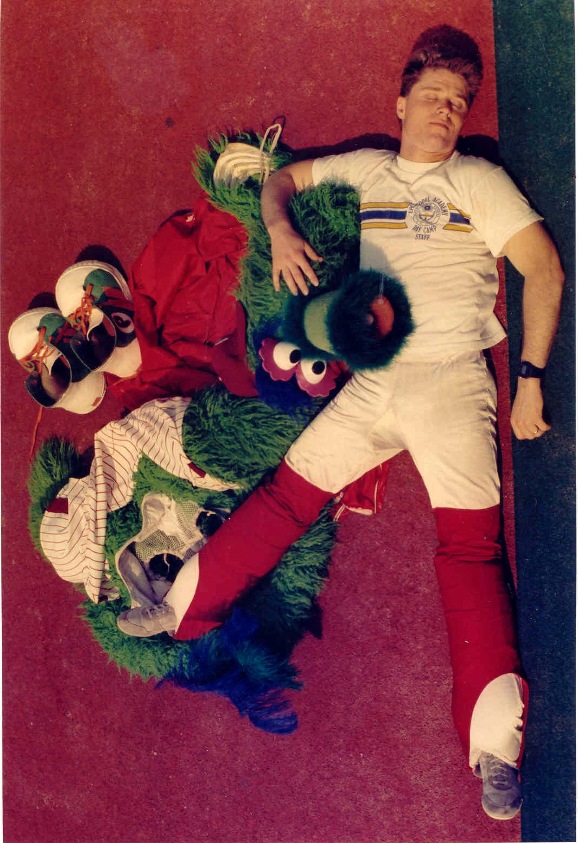

The man and his dream.

(photo courtesy of Dave Raymond)

Today Dave Raymond brings a lifetime of experience as a world-famous character to Raymond Entertainment Group, which designs and builds mascots for sports teams and even corporations.

REG focuses on marketing the Power of Fun. It’s not an easy trick to blend two seemingly opposite concepts like fun and business, but Raymond can speak from solid experience.

“I watched my kids become Phillies fans because of the Phanatic. They wanted to go to games because they had fun. And they learned how to watch baseball and appreciate baseball. My daughters fell in love with the players because they looked cute in baseball uniforms. And now they are not letting me leave when I want to beat the traffic. From a marketing standpoint, the Phanatic’s building baseball fans.”

So in dealing with clients, Raymond emphasizes how valuable—to their bottom line—their furry representative can be. The goofy character in a bird costume is a worthwhile business investment, and for it to pay off, it needs to be done right.

“The first thing we do is make sure they understand the difference between a kid in a costume and a character brand. A character brand is a living, breathing extension of your brand, and a kid in a costume is just that.

There’s even kids’ play areas dedicated to the Phillies’ enigmatic mascot.

“We research who they are in terms of the organization’s history, and who their community is in terms of the history. We help sketch out a back story that becomes the story of the character.

“They look at designs and they play Mr. Potato Head, they tell us what they like or more importantly what they don’t like, and then we go back and continue to draw until we get a design, we assign the copyright to that design, and then build multiple costumes for them. We help prime performers and train them.

“Also, what are you doing with the character brand? How are you rolling it out? How are you trying to get sponsorships? By the time we roll out the character, they should already know when they’re going to make all their money back, and when they’ll start making a profit.

“If they don’t do due diligence, frankly, I don’t want them as a customer. If they don’t want the best, they’re not gonna value the best.

“There are people saying I need a kid to get in my suit; right away I know that’s probably a client I don’t want. This is a character costume, it’s not a suit. It’s not a kid, it’s a trained performer. If you don’t want that, we’re not the ones for you. It’s a good thing not to waste time trying to make people buy from me. You’re not going to be able to service everybody.”

That’s not to say that REG doesn’t have a long list of satisfied clients; happy customers include the Cincinnati Reds, whose mascot “Gapper” is an REG creation, the Toledo Mud Hens, the Delmarva Shorebirds and the Phillies affiliate Lakewood Blue Claws, among many others. Raymond estimates that REG has created over a hundred characters, including at least ten for corporations.

“What separates us is that no one has the track record of success that we’ve had for not only designing and building, but also helping clients make money, drive revenue and brand, find performers and train them.”

Iconic enough to have his own mural at Citizens Bank Park.

It’s a seemingly natural progression for Raymond: from being an eager young intern who spent sixteen years bringing an inimitable brand of fun to a community, to now supporting a family by showing others how they can do it too.

“I’ve been to a lot of business training seminars, and they always ask what your ‘why’ is. My ‘why’ is, I want my marriage to be great, I want my kids to have good parents, and I want them to grow up and get married and have a great family. Every time I get a check for something, I’m going this is great, now I can pay my salary, and I can invest in what’s important to me, which is my kids and my relationship with my wife.

“Also, I’ve been delivering this presentation, which is the life lesson that the Phanatic has taught me, how powerful fun is to building a family and raising kids or whatever you’re doing. Using fun as a distracting tool is so powerful.

“That’s truly what I love doing more than anything else, getting in front of people and telling these stories and hopefully giving them something that helps them. I’m focused on going into Philadelphia, in the corporate community, and preaching the Power of Fun.”

If anyone knows how to appeal to sports types in the City of Brotherly Love, it’s Dave Raymond. After all, he’s lived it.

“One of the things I miss the most about not working as the Phanatic is the connection to the Philadelphia fan base. Once Phillies fans love you, they love you forever, and it’s almost impossible to do anything to get to the point where they don’t love you.

“That was the beauty of being the Phanatic.”

“I’m sorry sir, but your odor is scaring the kids.”

“This Costume Stinks!”

One service that Raymond Entertainment Group offers is costume cleaning…a surprisingly neglected aspect of mascot performance for many teams. The cleaning includes a “State of The Fur” analysis. A performer in a smelly costume is not a pleasant one, as Dave notes.

“The Phanatic opportunity for me, it truly was the best job you could ever imagine. But there were things about it that I hated. I hated that costume getting beer spilled on it, for example. I’m very anal retentive, I can’t stand things out of place, and it just drove me crazy. So I was meticulous about how I cleaned that costume.

“The first year, the people in New York that built it said they couldn’t wash it. You couldn’t even imagine what it smelled like. I finally just threw the thing in my bathtub with Woolite. I thought, I don’t care if I ruin it, it can’t smell like this anymore. When I got done cleaning it, it smelled great, and I wrote a note to the people in New York saying hey, this is how you clean it, and they were like, wow!”

Dave actually will frequently take on the cleaning tasks at REG. “This is what small business is about. I’m cleaning a lot of costumes myself. It’s just something that doesn’t require any great skill; you just spend a little time doing it. I have people that help and clean and restore the costumes. But I jump in there and do it a lot. It’s one of those healthy distractions for my mind.”

The “State of The Fur” analysis is for advice on cleaning and storage. “We try to give them feedback on what we all think they’re doing based on what is wrong with the costume. We want to have our eyes on it, because then our costumes last longer. Then people will say hey, when you get a costume from Raymond Entertainment it lasts for ten years.

“We prefer that rather than make money on rebuilding costumes, although we do that. It’s better that they know that their costume lasts three times longer than the competition.”

You too can dance on home team dugouts!

Mascot Boot Camp

Although Raymond Entertainment Group trains performers as part of their character creation package, Dave Raymond also hosts “Mascot Boot Camp”, where performers spend a weekend learning all about the business of being a character in a costume and non-verbal communication. It’s for everyone from new mascots learning the trade to longtime performers looking to rehabilitate their skills.

“It’s a great reality experience. If you want to experience what it’s like to be a mascot, come and experience mascot boot camp,” Dave says. “We’ve never marketed it for that, but it’s a lot of fun and they learn to move and communicate non-verbally, they learn how to take care of their costume, and learn how to take care of themselves physically.

“It’s a deep dive into mascot performance, there’s a real method to it now, where once it was Bill Giles telling me to go have fun.”

There’s another important rule of mascot performance: keep it safe.

“Lighting yourself on fire and jumping off a building and crashing into the ground might be something that people will talk about from now until the end of time, but you’re gonna kill yourself. And you’re gonna ruin the costume.”

REG’s “Angel Investor” – Sir Charles

Every business needs capital to get off the ground, and when Dave Raymond sought an investor for his idea to design and build characters, he found what he calls an “angel investor” who is well familiar with Philadelphia sports…Charles Barkley.

“When he would come to the Phillies games,” Raymond says of Sir Charles, “he would have fun with the Phanatic and we did a couple of routines here and there, where he was smacking the Phanatic around. It was fun. Charles invited me to hang out with him and some of his friends in Birmingham when I was doing minor league baseball in Birmingham one weekend.

“I just called him up, and he said my financial guy likes it, I’ll be happy to do it. His financial guy said listen, people haven’t paid Charles back over the years. I said, well, I’m dedicated to paying him back. I haven’t paid him every cent back, but he keeps telling me don’t worry, it’s no big deal. Charles just wanted to help. In the description of an angel investor, Charles Barkley’s picture should be in whatever dictionary or manual that is talking about angel this or that.

“Nobody knows that sort of thing. Charles has done that hundreds of times, he’s just a generous guy, one of the best people on the planet. I’ll be working until I close the business down to make sure he gets every penny back.”

Franklin has worked hard to get where he is today.

(photo courtesy of phillyfamily on Flickr)

Analyzing “Franklin”

Dave Raymond did some consulting for the 76ers in the rollout of their new mascot, a blue dog named Franklin. The humorous back story of Franklin on the 76ers website shows Franklin’s “ancestors” throughout Philadelphia history, including a missing bite out of Wilt Chamberlain’s “100” sign following Wilt’s 100-point game.

Raymond believes Franklin will be a success, despite the recent “controversy” surrounding the character—that Darnell Smith, who wears the Franklin costume, was a Knicks fan.

“One of the things he said to me was, I really need to be a Philadelphia fan, you gotta help me with who the Philadelphia fans are. He worked for MSG, and he was a mascot for the Liberty, the WNBA team. He’s done a lot of work with their performance team, the dunk team, all of that for the Knicks.

“Darnell is an awesome human being and an unbelievably gifted performer. I went to the first game that he was at just a couple of weeks ago and brought my kids, and he was kind enough to come up and interact with us. All the fans in our section were screaming for him. It was for kids by kids, which is what Tim McDermott said he wanted to do.

“What’s nice about it is that he recognized that getting in touch with the psyche of the Philadelphia fan was important. That just shows what a good performer he is. He’s an asset to the 76ers organization, I’m glad they got him.”

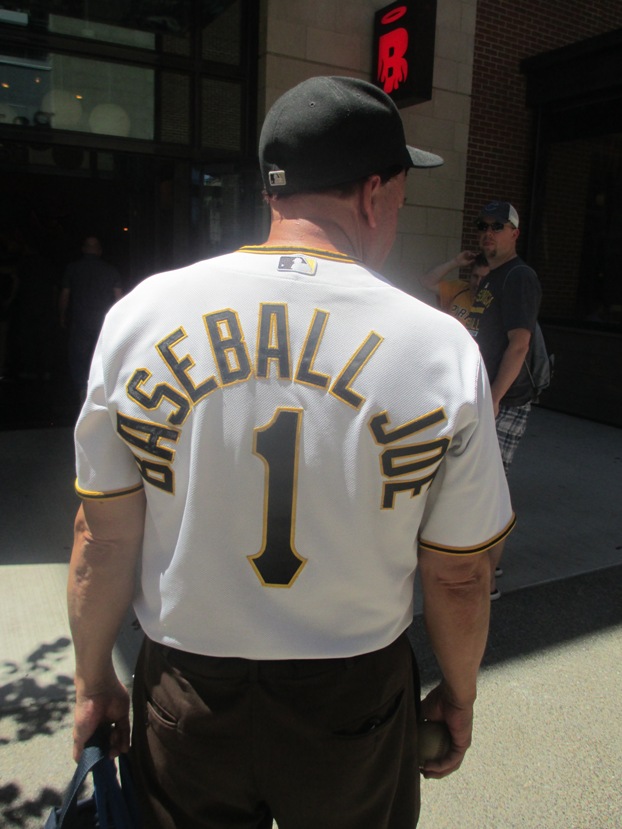

Keeping Up With Baseball Joe

I first met Baseball Joe Vogel on June 12, 2016, while meeting up with friend and fellow baseball road tripper Dan Davies and his group of traveling friends, who invited me to join them in Pittsburgh. He’s become a good friend and I always meet with him when I’m in Pittsburgh.

Baseball Joe (center), with Brazilian baseball fan Francisco Dornas (left), Dan Davies (lower right), and the traveling crew.

It was a picture-perfect day at stunning PNC Park, as the Pirates prepared to battle the Cardinals in a late afternoon matchup.

On this day, though, baseball isn’t the only thing on the mind of the Bucs faithful.

Sidney Crosby and the Penguins are in San Jose this evening, set to seal the deal on a fourth Stanley Cup for the city. Which they would, a few hours after the ballgame ends. Penguins jerseys, tees and caps can be seen in large numbers for a baseball crowd.

At one point during the game, a young fan brings out a mock, almost-life-size aluminum foil Stanley Cup and parades it proudly around a section in the right field corner. It gets a round of sustained applause from the excited fans sitting in the area.

But despite being a Pittsburgh native from birth, Joe Vogel is having none of this.

Without warning, as if duty calls him, he springs from his chair in the right field cove and disappears into the concourse. Seconds later he can be seen roaming the section where the Cup-carrying fan was. To the great amusement of his buddies in the cove, Vogel spends several minutes determinedly searching for the fan, who by this point is long gone.

The laughter in Vogel’s section grows louder as his determined search continues well beyond the amount of time one would think the situation warranted. Because after several innings of sitting with this character, they know exactly why he is seeking out the proud hockey fan.

It was to shame him. To frown on him. To educate the young lad on priorities.

Because as Baseball Joe Vogel will always let you know, only baseball matters. Every other sport is a waste of time.

The only fan that can throw a baseball around in a concourse and get away with it.

Baseball Joe is deaf and mute from three debilitating strokes. He communicates through gestures and hand signals, with a small keyboard, or on a folded piece of paper with the alphabet on it.

He lives in an apartment in downtown Pittsburgh, a short walk across the Clemente Bridge from PNC Park. Baseball, Pirates baseball, is his life. It has been since he was a young boy. He proclaims himself the “biggest baseball fan anywhere”, and thus far in my near half century of existence I haven’t met a bigger one…which, if you knew my father, is saying something.

The Pirates know him well. He occasionally plays catch with manager Clint Hurdle and even advises him at times via e-mail. Courtesy of a team that loves his dedication, he has season tickets and attends every game in the covered handicapped section in right field, underneath the right field bleachers. He can’t be in the sun for too long. He may be the only fan in PNC Park who doesn’t care about the picturesque city backdrop.

Sitting with him, it’s almost impossible to pay attention to the game, especially as opposing hitters tee off on Pirates pitching as the Cards would that night. Baseball Joe is every bit as entertaining as the action on the field…constantly having conversations with bystanders in his own way, patiently communicating with his keyboard or well-worn piece of paper when people have difficulty understanding his gestures.

He carries a baseball that he frequently tosses to passing ushers, who nonchalantly toss it back to him, knowing the routine. Throughout the game, other team employees stop to greet him. He constantly collects souvenirs and seems to have a never-ending supply of the large soda cups, one of which he shares with me.

Baseball Joe with his essential ballgame supplies.

Throughout the evening loud laughter is heard in the section at both his knowledge of baseball and his chastising of fellow fans for their comparatively insufficient reverence for the game.

At one point, he asks me if I like any other sports. Forgetting his disdain for the hockey fan, I tell him I like NASCAR too, and he shakes his head. He pretends to be driving a car, and then frowns at me and does the shame symbol with his fingers. He then holds up a baseball and makes a circular motion with his finger. By this point it’s understood. Baseball, year-round.

All night long, it never stops. With his keypad, he fires baseball trivia questions at his buddies…like “Name two players in the Hall of Fame that have the same first and middle names.” A wiseacre in the group replies, with great bombast as if he’s sure of the answer, “Ken Griffey Senior and Ken Griffey Junior!”

As the rest of the group laughs, Joe smiles, turns to me and informs me: Henry Louis Aaron and Henry Louis Gehrig, or Joseph Paul DiMaggio and Joseph Paul Torre.

Later Dan, who took Joe along with his group to several ballparks and the Hall of Fame, told me the story of his wiping up the floor with an interactive trivia game at the Hall. If there was a baseball edition of “Jeopardy”, Baseball Joe would be Ken Jennings.

Home of Baseball Joe.

Baseball Joe holds the distinction of being the first fan to ask for my autograph, at least as an author of baseball books.

At the Pirates game, he asked me to send him the PNC Park E-Guide…and to autograph it for him. He also gave me firm instructions…make sure I sign my full name, middle name included, and do it neatly, which I am not accustomed to doing with my usual chicken scratch of a signature. He’s a stickler, this one, especially when it comes to matters baseball.

Joe loved the E-Guide and raved about it to me in an e-mail…a badge of honor…but he also had a few suggestions: elaborate more on seating, include some photos in the whitespace, and maybe talk more about food and such. He is the first fan ever to complain to me that there isn’t enough information in a Ballpark E-Guide.

He has been repeatedly asking me to send him guides for Wrigley and for Busch in St. Louis, should I ever write that one. I will. I’m always happy to have an audience.

Citizens Bank Park from the west.

A few days after the Pittsburgh experience, I met up with Baseball Joe and the group again, this time in Citizens Bank Park in my hometown of Philly. I found them a free parking spot and sat with them in the upper level for the evening. Throughout the evening, Joe kept me entertained, once again more often than the action on the field.

I tell him I am an Orioles fan, and he holds up fingers…first seven and then one. I immediately get it. 1971 World Series. Pirates over the Birds in seven. I was three.

Then he makes a “7” and a “9” with his fingers. 1979. The Pirates, led by Pops Stargell and rallying around the passing of manager Chuck Tanner’s mother, come back from 3-1 to once again beat the O’s in seven games. My response is to hang my head and to pretend to rub tears from my eyes, illustrating the heartbreak of the 11-year-old Orioles fan that year. “I still NEVER dance to ‘We Are Family’”, I inform him.

He nods, understanding. He does the eye rub himself when he brings up the Pirates’ long stretch of down years.

He asks me who my favorite player is, and when I say Cal Ripken Jr., he quickly replies on his keyboard with a stat for me: “Lowest batting average of any player with 3,000 hits”. Sigh.

When I show Joe a picture of my daughter posing with baseball-themed stuffed animals that I’ve brought home for her from my travels, he briefly types on his keyboard and shows me. “You so blessed,” it reads. “Me haves no family.”

I instantly feel both sad for him and guilty about the occasional dissatisfaction I feel with my own life. He’s right. I am so blessed. I not only have two beautiful and healthy kids, I still have time for the only sport that matters.

Baseball’s #1 fan.

Long after the crowd has filed out of Citizens Bank Park that night, Baseball Joe manages to make a few ushers uncomfortable with his refusal to leave the seating bowl before collecting as many souvenir cups as he can. You can see clear agitation growing in the ushers’ eyes as they anticipate a confrontation. Joe seems oblivious to the approaching ballpark police, but he exits the seating bowl at what seems the exact moment before the ushers turn snooty. He’s a pro at this.

Back at the hotel where the traveling fans are staying, Baseball Joe and I pose for a picture, and he surprises me with a huge bear hug. Apparently I’ve made a good impression. I’m grateful that he’s not upset with me for showing him family photos.

Joe and I e-mail each other frequently. In his e-mails to me the subject line is almost always “Baseball 24 7 366”—making sure he’s covered in leap years. His e-mails are usually brief but always thoughtful…wishing my family a great holiday season, asking me to send along more E-Guides when I can, and sharing his thoughts on the Pirates’ fortunes. Shortly after the Pirates failed to make the playoffs in 2016, he sent me an e-mail with the words “Pirates eliminated – me cry” in it. For 33 years and counting, this Orioles fan has known the feeling.

I’m always grateful to hear from him. Because whenever I reflect on it, he’s right. Other sports are a waste of time.

And Baseball Joe knows as well as anyone that our time is too valuable to waste.

Did this post make your day a little bit?

I hope so. If it did, I would really appreciate your support.

When you use this link to shop on Amazon, you’ll help subsidize this great website…at no extra charge to you.

Thanks very much…come back soon!

Beepball Wizards – The Boston Renegades

When a magazine suggests you write a piece about blind baseball players, you have to take on the assignment just to see how in the wide world of sports such a thing is possible. But indeed it is, and I covered the Boston Renegades for the Summer 2019 issue of BostonMan. You can read the article on their website here, or see the magazine article PDF here.

Beepball Wizards

The Association of Blind Citizens Boston Renegades are a powerhouse in Beep Baseball, a form of baseball played by legally blind people.

On the website for the Association of Blind Citizens Boston Renegades, the local Beep Baseball team, you can find a short video trailer for their documentary.

In the video, mere seconds after one player tells his heart-wrenching story of being literally struck blind, coach Rob Weissman is seen reprimanding his team. “You guys are going to pay for this bad practice,” he informs them. In another scene he lectures to a player, “Life isn’t fair. I worked my ass off when I played ball. I got cut every friggin’ time.”

Imagine telling a blind person that their desire is questionable. Talk about tough love.

But that’s exactly the point. At the end of the video, that same coach is seen firing up his players before the game, reminding them what success on the field is about. It’s about respect.

Rob Weissman cares enough to take a team of blind baseball players at the bottom of their league and mold them into dominant yearly contenders. In the last three seasons, they’ve compiled a 40-8 record and played in a national title game.

As coach says of the endeavor, it’s about more than winning games. It’s creating a culture of working together to achieve goals.

Rob Weissman isn’t as rough as he appears to be. He’s just a good coach.

When asked about the video, Weissman chuckles knowingly, as if he’s fielded the question a few thousand times. He gets that it’s dramatization and that a viewer’s reaction is exactly the goal of the trailer, but he’s nowhere near that hard-nosed coach that comes across in a small few captured moments. “It’s a teaser,” he asserts for the record. “If I was that tough, no one would be with this team.”

As he explains, there was a desire to change the team culture at the time, and someone needed to take the bull by the horns and lead the way.

“They made a decision that they wanted to be competitive, but a lot of them had never been part of a competitive team. So a lot of learning needed to happen. It wasn’t going to be ‘let’s go get pounded by the top teams in the league, and everyone’s going to love us, because they’re going to beat the crap out of us and we’re going to pay for the beers afterwards, which is what it was early in the history of the team.

“I said, look, I’ll be able to get this team up and running and I’ll be able to bring in great volunteers, but we have to change the culture.”

It’s worked. Weissman and his staff…he is quick to credit team owner John Oliveira, coach and pitcher Peter Connolly, pitcher Ron Cochran and coach Bryan Grillo among others…have created a winning atmosphere in Boston beepball. All with home grown talent.

“I think that we are the only team in the history of the league to go from being the doormat of the league to making a title game, only using players from our roster,” Weissman notes. “A lot of other teams will bring in people from other cities. We’ve never done that. Every one of our players has grown up in our system. We’re really proud of that.”

Sometimes working your ass off is worth it.

Baserunning is equally important in Beep Baseball.

Baseball for the blind. The words invoke instant confusion. Of the senses most needed to play baseball, vision easily tops the list.

Before you ponder how it’s possible for a someone to play baseball without seeing, consider this: there is a nationwide league. The National Beep Baseball Association features teams not just in Boston, but also in Chicago, Vegas, even Anchorage. There are 35 NBBA teams in all, and yes, there is a World Series.

Beep Baseball works like this: all players except the pitcher and catcher are completely blindfolded, to play on the same vision level despite their degree of blindness. The ball is softball-sized and is built with a beeping device in it, so defensive players can field it by following the sound when the coach calls out the fielding formation.

Batters are given four strikes, and the pitcher plays for the offensive team. The pitcher calls out to the batter when the pitch is thrown, and attempts to put the ball in the batter’s swing zone. If the batter makes contact and manages to hit the ball at least 40 feet, the defensive team moves to field the beeping ball. A ball hit further than 180 feet is considered a home run.

There’s no baserunning in the traditional sense. After contact, the batter runs towards one of two pylons that serve as bases, whichever one is buzzing. If a batter reaches the pylon before the ball is fielded cleanly, a run is scored. If the ball is fielded cleanly before the batter makes the bag, the batter is out. Games last six innings, or more if needed.

A contact hitter.

It’s easy to argue that a professional ballplayer hitting .350 is one of the most impressive achievements in sports. But even with a pitcher grooving the ball in a batter’s swing zone, it’s pretty impressive to see a blindfolded batter put a ball in play. If someone claimed that the Force was strong in better hitters, it wouldn’t be difficult to believe.

Peter Connolly, a pitcher and coach for the Renegades, explains the mechanics, and how hitters learn and improve their skills.

“It’s a combination of knowing your swing, being consistent, just honing in on your consistency. Maybe getting a little more power, maybe being able to go the other way in certain situations.

“If you can pop the ball up in the air for four seconds, you have a really good chance of getting to the bag. That’s another thing that you can hone onto, base running and getting faster. If you watch the good teams in the World Series, they have such speed that if they hit the ball and you don’t field it perfectly, it’s too late.”

Weissman agrees that just as with any sport, the skills can be learned. “We’ve all learned a lot over time about how to coach the sport better. And we’re constantly working on hitting mechanics.

“Joe Yee hit like 400 points higher than his career batting average last year. Some of that was him learning how to improve his individual skills, and being coachable enough to learn about how to move his hands, to be more aware of his bat path, to learn how to transfer his weight.”

Yee, incidentally, is Connolly’s cousin, and it’s an impressive pitcher-hitter battery.

“I think he was batting like .600 or something off of me last year,” Connolly says.

Weissman leading a newly inspired Renegades club.

Despite that Rob Weissman disavows his appearance as a tough coach, he does point out that players on his team want to be treated like athletes, not disabled people.

He amusingly remembers the story of Steve Houston, a former college ballplayer who lost his sight to diabetes, growing visibly annoyed and chewing out a pitcher for “babying” him when he learned the pitcher was throwing underhand to him. It’s impossible not to admire the mental fortitude of a player who believes he can handle a high hard one while blindfolded.

That said, Weissman knows there are limits in some cases. The Renegades don’t cut players, and anyone who is willing to make the financial and time commitment can play.

“One of our players, Melissa Hoyt, has Mitochondrial disease. It makes it very hard for her to breathe at times. We have another player named Rob, doctors told him he’d never play competitive sports. He’s a diabetic, so they’ve got other issues. We can’t put them out and play them 18 innings in a day. I know that they’re not gonna make it through warmups without having to take a break.

“But they’re great teammates. They’re very supportive and everyone’s very supportive of them. One of the most memorable moments that we had last year was when Melissa, who’s been with the team for a very long time, scored her first run. Every single coach and player on the team was just fired up about that.

“One of the things that’s so cool and unique about this team is just how everyone supports each other. And that we get wins in various ways.”

Play hard. Represent your city.

Back in 2003, Rob Weissman, John Oliveira and company had a vision. To give blind citizens in the Boston area a chance to come together and achieve something special, through baseball of all things.

Mission accomplished.

“When we took the field in the championship game,” Rob reflects, “for me, I think that was one of the proudest moments. It was like the Red Sox winning in 2004. And we wouldn’t have gotten here without the help of every single coach and player, past and present.”

Does Rob Weissman see a World Series victory in the Renegades’ future?

“I’d love to sit with you and say, our goal is to win a championship. But I think our goal every year is to be the best that we can be.”

Did this post make your day a little bit?

I hope so. If it did, I would really appreciate your support.

When you use this link to shop on Amazon, you’ll help subsidize this great website…at no extra charge to you.

Thanks very much…come back soon!

The Book of Beep Baseball

David Wanczyk, an English professor at Ohio University, was enthralled enough by the idea of beep baseball that he wrote a book about it, Beep: Inside the Unseen World of Baseball for the Blind.

In it Wanczyk chronicles the history of the sport, and documents the adventures of beep baseball teams, including the Renegades and Weissman’s fanatical dedication to coaching and winning.

Here’s a passage from Wanczyk in the book about Weissman:

“Like any manager, he’s concerned about injuries, field conditions, the umpires, the draw. And like some, he’s battling precompetition butterflies, otherwise known as chronic indigestion. Weissman doesn’t really eat, and when he does, he eats Pop-Tarts, two or three a day, like a college-student gamer somehow gluing together his wild thoughts with hard frosting. But Lisa Klinkenborg, the Renegades’ resident trainer/nutritionist, has forgotten to buy his Pop-Tarts on her grocery run, unf***ingbelievable, and he’s not sure where his next meal is coming from. He’s really not sure anymore.”

Wanczyk tells BostonMan this about Weissman: “He certainly stresses about the game, let’s say that. He’ll probably tell you more. And if you have trouble getting him to tell you, you can mention that my book says something about this and that I make the connection between his efforts and his health. If he wants to dispute that connection, he’ll probably do it in a colorful way!”

But Weissman isn’t the only dedicated one, as Wanczyk and his book point out. Beep Baseball features all of the intense struggle of competition within limits.

“The action on the field is fast-paced, and you’re watching dare-devil sorts of diving and colliding. But once the inning is over and the players make their way back to the bench, they will often move pretty slowly, listening for the voices of their coaches, or even finger-snaps to help them get to the bench.

Wanczyk makes the interesting point that “beep ball is about pushing limits, but those limits are part of the game. If a player runs as hard as he wants to, he overruns the ball. Blind people can do a lot, but they still have to do it deliberately, and coincidentally, that patient speed is the best way to succeed in beep ball.

“In Boston, we’ve always liked baseball underdogs. The Renegades are an underdog, and they’re always rallying.”

If you’re interested in a copy of Beep: Inside the Unseen World of Baseball for the Blind, it’s available on Amazon or at www.davidwanczyk.com.

They play hard, like any Boston team.

Support The Renegades

The Association of Blind Citizens in Boston currently operates the Renegades, and being a non-profit, they are always looking for volunteers, players, and donations. Rob Weissman says they have some creative ways to fund and operate the team, but they can always use help.

“Some of our volunteers, they work for big name companies. Like myself, I work for IBM, one of our volunteers, Aaron Proctor works for JetBlue. JetBlue and IBM are also very big proponents of volunteerism, so they’ll support us and donate money to the team or in JetBlue’s case, they’ll donate plane tickets to the team.

“The Challenged Athletes Foundation is an amazing organization; they allow players to apply for grants and they have been extremely generous and supportive. About seven or eight of our players were able to get almost $750 each out of the challenge that so that gets them halfway there on their fundraising.

“Regionally we travel with between 20 and 30 people. That’s a lot of people to put into hotel rooms. If you’re willing to donate to a cause, our budget’s $20-25,000 a year and any little amount helps.”

In addition, Coach adds the most important thing the Renegades need…volunteers and players.

“We’re always looking for great volunteers, if people have baseball skills, or time or any skills that they could offer. We’re always looking for people. This team would not survive without volunteers.

“At the same time, if you know somebody who’s visually impaired, we’re the only team sport that exists in Massachusetts. Have them get in touch with us and come try it out. It’s amazing, so many of the guys get so much out of it other than just playing sports. This goes well beyond baseball.”

If you’d like to make a donation, volunteer, or get the Renegades in touch with a blind person interested in playing ball, you can visit the website at www.blindcitizens.org/renegades.

Christian Thaxton, with the sweet swing that brought his bat to Cooperstown.

Making Cooperstown

The Boston Renegades’ website includes their top ten moments of the 2018 season. At the top of the list is their visit to the Baseball Hall of Fame, to see the exhibit of Christian Thaxton’s bat. There is a video of Thaxton, the top hitter in the history of the league, being shown the exhibit.

A year later, Weissman’s voice still cracks a bit telling the story.

“Baseball was in his blood. He played high school ball, he ended up getting onto a junior college baseball team and then finding out that he couldn’t see the inside fastball anymore, and that was the pitch he crushed.”

Thaxton went to see an eye doctor and was informed he was going blind.

“He dusted himself off quickly. He made a decision that he was going to come to Boston to learn skills to be a blind person, to go into the Carroll Center for the Blind in Newton.”

At the Carroll Center, he heard about the Boston Renegades, and it turned out he could still hit a baseball pretty well. Enough to make him want to stay in Boston.

“When he set the record for the highest batting average in the history of the league, Cooperstown came calling and said, we’d like to put his bat in the Hall of Fame. And last year, being with Christian and seeing him see his bat in a display case in the Hall of Fame, after everything that he’s been through, was amazing.”

And well deserved.

“Christian isn’t the type of athlete who’s all about himself,” Weissman adds. “He has taught so many of his teammates proper mechanics to swing. He takes such great joy out of seeing his teammates succeed. That’s who he is as a person.

“To give him the opportunity to see his bat in Cooperstown was unbelievably heartwarming.”

(all photos for this piece are courtesy of Rob Weissman, Lisa Andrews, David Wanczyk, and John Lykowski Jr.)

This post contains affiliate links. If you click on the links and then make a purchase, the site owner earns a commission at no extra cost to you. Thanks for your support.

Why Don’t The Rays Draw?

Why don’t the Rays draw? Despite an AL championship in 2008, a division title in 2010, an exhilarating wild card win in 2011 and a playoff appearance in 2013, the Tampa Bay nine never seem to be playing to a full house, or often even a half-full house.

Even in the last game of the season in 2011, arguably the biggest regular season game in franchise history and with the Yankees in town bringing their own fans, only 27,000 people passed through the gates.

Chances of catching a foul ball? Excellent.

The Rays have been playing exciting baseball in recent years, and doing so with a fraction of the payroll (and ticket prices) of the Yankees and Red Sox. Yet they almost never sell out the Trop, and are consistently among the worst in team attendance. It’s a sad indictment of the market, unfortunately, because there’s nothing lacking in the dedication of existing Rays fans. Their TV numbers are as good as most teams.

I’ve read a few things about why the Rays don’t draw well and have my own opinions on it. I think it’s a combination of several factors.

First is the venue. Tropicana Field is not the most baseball-friendly place to see a ballgame. It’s indoors, concrete, has artificial turf and generally has a sterile feel to it. The Trop is the last non-retractable roof dome in baseball, and it’s one of only two with plastic turf (Rogers Centre in Toronto is the other, and even Rogers may have grass soon). Florida is the Sunshine State…who wants to go where there is no sunshine, for a ballgame of all things?

The sign should include “where most of the fans are”.

Second is the location of the ballpark. The Trop is in St. Petersburg, a fairly good distance through heavy traffic from Tampa, where a good portion of the population center of the market is.

Tampa residents do not particularly like the drive to the ballpark from what I’ve read, which can take a long time during rush hour…which, in theory, is when everyone would be going.

Third is the market in general. Many Florida residents are transplants, and as such are fans of the Yankees, Red Sox, Phillies or another northeast team. The Rays are a relatively new team, and up until 2008 they were perennial cellar-dwellers in the American League East.

While the turnaround has been very impressive, a few competitive years don’t exactly make the Rays a storied franchise, and a local fan base still dedicated to other teams won’t grow so quickly.

Finally, not many people point this out, but no baseball venue in North America has so few options for getting to the ballpark.

It would be nice if they had one of these in Tampa.

The Trop is easily accessed by car, but there are few trains or buses to speak of that will take riders to the game on a nightly basis. There are some novelty options like the Brew Bus and Rally Bus, but nothing resembling the Red Line in Chicago or the Broad Street Line in Philly.

On top of that, many locals will tell you that the drive from Tampa and its suburbs to the Trop is brutal on weeknights.

The Pinellas Suncoast Transit Authority does currently have bus routes that stop at or near Tropicana Field; it is in the heart of downtown St. Petersburg so that isn’t difficult to do. The problem is that none of the bus routes can be used for night games; most buses have their last run from the area at around 10:30 or so, which might be doable but would certainly preclude seeing extra innings.

So the Rays have all of this going against them, and the last three reasons may have been why baseball was reluctant to encourage the Tampa Bay area government to build a stadium to lure a team back in 1990. They built the then-Suncoast Dome anyway, and were cruelly used as leverage for the Giants and White Sox before baseball awarded them the Devil Rays in 1998.

The big white dome.

So what can the Rays do? Perhaps the Rays could provide such a shuttle of their own for a reasonable fee, which would be much easier to market. (They do from from the nearby pier to add some parking options, but that’s it.)

If the Pinellas County government is in a good mood, they might even create a separate lane for the Rays bus on game nights. It could stop at several locations within the city and suburbs, and be available in case people need to leave early.

Or they could work with the PSTA on providing such a shuttle; they already have routes in place with a long reach in the area.

Then there is the venue. The Rays are rumored to be pushing for a new ballpark; but you never actually hear anything concrete from Rays management. They signed a lease when arriving in Tampa Bay, so presumably they’re at Tropicana Field until 2027. But we all know contracts don’t mean squat when there’s millions to be made for team owners and municipalities.

They should sell tickets for the catwalks.

Could the Rays afford to turn Tropicana Field into a retractable roof dome? I can’t say how hard that would be, but I imagine it could be done. A dome is great in Florida summer heat or the nasty thunderstorms, but no one wants to go inside to watch a ballgame on a beautiful 80-degree April day.

Guaranteed Rate Field in Chicago, Kauffman Stadium in Kansas City, Angel Stadium in Anaheim and Fenway Park in Boston have all undergone significant changes, generally costing less than what a new ballpark would cost. I expect taking the roof off of the Trop would be much harder, but replacing it with a retractable roof and replacing the turf with grass would go a long way to making the Trop a much more appealing venue.

That, however, is a very long shot. The team may convince St. Petersburg to let them out of their lease, and get a new ballpark built in Tampa, but thus far that is a no go with St. Petersburg folks, and probably rightly so.

Regarding the market and the transplants, the Rays may not need more than a few more years of quality baseball to turn the tables in their favor. After all, if you can see a team capable of beating the Yankees and Red Sox for as little as $9 for a game and park for free, fans have incentive to take their children to the game.

It stands to reason that younger people especially may grow fond of this team over time, especially before they start to travel and see superior ballparks. The Rays’ ticket affordability should help with that…as more parents bring their kids to the game because they can, the Rays may be gradually building a future fan base.

Looks friendly enough, right?

Some cities just don’t do well as a baseball market. Atlanta does well enough, but you would think for all of the team’s success that they would draw better than they do. Miami hasn’t proven it wants a team yet, even with a shiny new retractable-roof ballpark.

There are a few answers to the question of “why don’t the Rays draw”. But I don’t yet accept that the Rays won’t ever fill their ballpark to capacity every night someday. If this team keeps playing competitive baseball and finds a way to bring the far-flung fans in, they may yet turn around their attendance problem.

I’d be cool with that. I like the team’s colors.

Did this post make your day a little bit?

I hope so. If it did, I would really appreciate your support.

When you use this link to shop on Amazon, you’ll help subsidize this great website…at no extra charge to you.

Thanks very much…come back soon!

What Happened To The Montreal Expos?

Like most baseball fans, I didn’t know the full story of what happened to the Montreal Expos. When I read a bit about it, it turned out to be very different than what I thought.

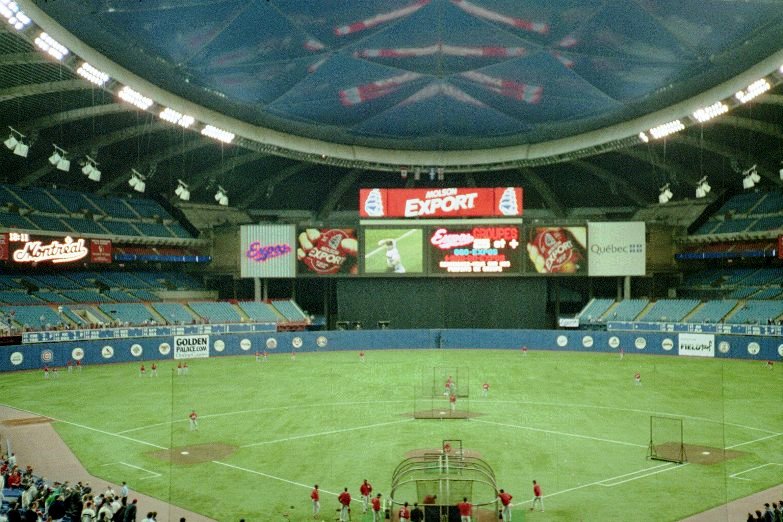

In May of 2004 I took a long weekend and made a trip to Montreal, to see a game at Olympic Stadium before the Expos moved to Washington to become the Nationals.

I made it to the top before I realized there was an elevator.

I had a very enjoyable time in Montreal. First there was the very pleasant ride on I-87 through parts of New York state that people don’t know about, and the even more enjoyable ride home on 9N. And Montreal is a neat city—there is Mount Royal and its terrific view of the skyline, the smoked beef sandwich from Schwartz’s, the fine public transit system, and the incredible Notre Dame Basilica cathedral, a church so stunningly beautiful that I did not bother trying to do it justice with photos.

So being in a city that I held in fairly high regard, it was sad to see how interest in baseball was barely moving the needle. The game I attended was against the Cardinals, and it drew a crowd of about 5,000—probably 2,000 of which were Cards fans. The Expos won an exciting contest with the help of star shortstop Jose Vidro, and I remember hearing a radio show afterward with the host expressing hope against hope that the city could keep its baseball team.

When lower level sections are blocked off, there’s a problem.

The Expos’ departure from Montreal is often summarily dismissed as being the result of the city being obsessed with its hockey team and just not caring about baseball. I thought this myself before taking an interest in the subject recently, and not only was I completely wrong, I’m firmly of the opinion that the second largest city in Canada deserves a baseball team.

Baseball in Montreal drew some nice crowds once—the Expos even outdrew the Yankees for a couple of seasons in the 1980s. The team was competitive in those years, almost reaching the World Series in 1981 and falling a game or two short of winning the NL East in a couple of other campaigns. The Expos finished second in 1980 and in 1993 to Phillies teams that happened to be loaded.

In 1994, however, the Expos front office had assembled the best team that Montreal had seen yet. This team featured Larry Walker, Marquis Grissom, Moises Alou and Ken Hill, and they had some pretty good arms on the mound, too: names like John Wetteland, Jeff Fassero, and a guy by the name of Pedro Martinez. By August, the Expos were leading the National League East with a 74-40 record. And we all know what happened then.

The announcer was really good at both French and English.

The strike of 1994, that killed the rest of the season and the World Series, instilled great anger in baseball fans everywhere, and it showed in the attendance in 1995. But it was particularly hard on Expos fans, who had possibly been rooting for the best team that had ever been fielded in their city. (Larry Walker believes unequivocally to this day that the Expos would have won the World Series.)

The Expos were drawing 34,000 a game at the time, not spectacular for a contending team, but certainly better than any attendance average figure the Rays have ever managed. And this in Stade Olympique, one of the most unappealing venues in baseball.

The strike was the first of several blows that would eventually drive the Expos out of town.

After a season that had given more hope to Expos fans than any season ever had only to deprive them of an ending, Expos’ owner Claude Brochu ordered GM Kevin Malone to slash the payroll, and the Expos started their next season without Walker, Hill, Wetteland and Grissom.

Depleted and discouraged, the Expos finished last in 1995. Soon afterwards, Alou, Fassero and Martinez would also be gone.

Paid attendance for this game: 5,332. They didn’t put that number on the scoreboard.

If you’ve ever been a fan of a team that has a fire sale after a winning season, you know what it does to attendance. Fans really, really hate that. For a team to lose two-thirds of its gate is not unusual. Imagine the effect on fans when the best team that the town had ever seen has been gutted. To add insult to injury, the fire sale happened in 1995…after the Blue Jays had won back-to-back titles, establishing them as Canada’s premier MLB team. It is something like the Red Sox having broken their long-standing curse a year after the Cubs fell just short of breaking theirs.

The Expos never recovered. Jeffrey Loria, arguably the most unpopular baseball team owner in history (and that’s saying something), purchased the team in 1999 and instantly became reviled with fans by not renewing the team’s television and English-speaking radio contracts. From what I’ve read, the terms of the deal Loria wanted were such that their broadcast stations walked away from the table without even bothering to negotiate.

As a result, if you were an English-speaking Expos fan, your options to find out what happened in last night’s game were to go to the ballpark or read about it on the Internet or the paper. This isn’t something fans today are willing to tolerate, and nor should they.

Following this, Loria had the nerve to try to secure funding from the city for a new ballpark. Labatt Park had some interesting innovations…it wasn’t designed by HOK, so there were some new ideas…and for a while the team looked like it could get its wish. But eventually the premier of the province of Quebec, Lucien Bouchard, decided that he couldn’t in good conscience spend taxpayer money to build a new stadium in a city where hospitals were closing.

In retrospect, if Montreal baseball had been revived, the tax revenues the team brought in could have saved some hospitals, but the Expos couldn’t justify that with the attendance at the time.

So who is the beer sponsor?

The death of the ballpark deal probably convinced Expos fans that baseball in Montreal was now on life support.

Animosity towards the ownership—which eventually became Major League Baseball, so that Loria could buy a team in a city that would gladly spend taxpayer money for a ballpark for him—reached the point that by 2004 they were showing up in record low numbers, and 3,000-5,000 per game was common.

After being insulted and taken for granted on so many levels, Montrealers may have been wishing the Expos and Major League Baseball good riddance by then, but one could hardly blame them.

They had endured greed destroying their most promising season, along with ownership that was willing to sell off the team’s biggest stars and not allow fans to watch games on television or listen on the radio, and refuse to even try to negotiate with a city on new ballpark financing, which might have been possible had Loria been willing.

The blame for the Expos’ departure belongs not on Montreal fans as a group or Montreal as a sports market. Not in the slightest. A combination of factors that would have destroyed fan support in any city conspired to victimize a market that, until August of 1994, had been building a strong baseball tradition.

The strike of 1994 angered a lot of baseball fans, but ultimately the biggest victims were the fans in Montreal. It set the wheels in motion for the sad, drawn out ending, the only upside of which has been the return of baseball to Washington, D.C.

The movement to bring the Nationals back to Montreal!

Perhaps baseball will have an opportunity to return to the great city of Montreal; I hope so. As I hope I’ve illustrated here, to say the market won’t support baseball isn’t true.

Did this post make your day a little bit?

I hope so. If it did, I would really appreciate your support.

When you use this link to shop on Amazon, you’ll help subsidize this great website…at no extra charge to you.

Thanks very much…come back soon!

(Note: this article contains affiliate links. If you use an affiliate link to make a purchase, Ballpark E-Guides earns a commission, at no extra cost to you. Thanks for your support!)

Wheelchair Basketball – Rolling Thunder

I had never known that wheelchair basketball was as established as it was, with professional leagues and established teams, until JerseyMan asked me to cover it for their December 2014 issue. I had the pleasure of interviewing John DeAngelo, a player for the Magee Spokesmen of Philly, who filled me in on the rough and tumble nature of the sport. You can view the PDF from the article here.

Rolling Thunder

Think wheelchair basketball is a small time, friendly competition? Think again.

At the Carousel House in Fairmount Park, the Magee Spokesmen are wheeling laps around the basketball court at the start of their weekly practice session.

After a few dozen circuits, they gather at one end. They begin start and stop drills, rolling out to the center of the court, stopping on a dime, executing hard 180-degree turns, and pushing back in the direction of the net.

Their coach, Eric Kreeb—who by day is a kitchen manager at Chickie’s and Pete’s—stands by and watches, smiling and shouting words of encouragement. Slide right, he shouts, turn and get on the line. The drills continue. Men push, turn, and then go from one end to the court to the other and then back…backwards. They pant, strain and sweat.

Back at the line, they’re huffing a bit now. “Turning left this time,” shouts Kreeb. His direction is met with some mild groans of protest. But the Spokesmen oblige, rolling out, turning left and rolling back. To some, it’s a competition. “Get your money!” one player shouts repeatedly. Forward and backward, turning wheelchairs left and right, drill after drill after drill. The practice is almost an hour old, and no one has yet touched a basketball.

Finally, they start shooting, taking turns at the foul line. As they shoot, two players practice defending one another, maneuvering a specially designed chair with an ability that clearly isn’t learned overnight.

The team splits into two groups and gather at either end of the court. A scrimmage game begins. Wheelchairs clang into each other as players jockey for a position. Fast breaks happen, as do lay-ups, fadeaway baskets and rebounds. Players even occasionally fall out of their wheelchairs, but such incidents only briefly delay the action, and they are back up quickly.

One can only imagine the toll a whole game of this—or six whole games of this—would take on someone who isn’t built up for the battle.

“We prepare for our games at practice,” says Kreeb. “We do several stamina building drills, diagram plays, go over defense, and discuss strategies of attack against our upcoming opponents. The conditioning is particularly important because we play in tournaments. Most tournaments you play five to six games in two days.”

This is no playful, recreational diversion. It’s a real, honest team practice. It is the grueling, repetitive effort that athletes put in that makes their feats on game day look effortless. The Magee Spokesmen are professional athletes. It’s obvious by the way they miraculously avoid collisions and effortlessly land passes into teammates’ hands.

The focus of wheelchair basketball isn’t the wheelchair. It’s the basketball.

John DeAngelo, professional wheelchair basketball player.

The words “wheelchair basketball” to most people probably bring to mind images of a few guys sitting around shooting baskets in an ultra-friendly lightweight competition. The idea of it being an international sport, with leagues, divisions, and tournaments, would likely come as a surprise.

The sport began in veterans’ hospitals shortly after World War II, as paralyzed war heroes adjusted to their new life. As the sport grew and teams emerged across the country, the National Wheelchair Basketball Association was formed. Today the NWBA has over 200 teams in 22 conferences, many of them sponsored by local NBA teams.

Internationally, since the formation of the International Wheelchair Basketball Federation (IWBF), the sport has even more notoriety, particularly in places like France, Australia and Canada. Australia is the current IWBF men’s champion; Canada’s team took the women’s wheelchair basketball title this year.

John DeAngelo, a player for the Spokesmen, took the time to educate me a bit about the sport. Born with a congenital affliction, he has been playing wheelchair basketball since the age of 12.

“The first thing, leaving basketball aside, is just getting used to a wheelchair,” he says. “It sounds easy, but maneuvering a wheelchair is not as easy as you might think. Before you learn anything else about ice hockey, if you can’t skate, you can’t do anything. The players who really excel, it’s like the chair is almost an extension of their body.

“Then you start to throw in the sport part, dribbling a basketball and learning how to shoot and maneuver around people that are trying to defend you. The mechanics are the same way; you just take the legs out of it. The upper body mechanics are the same. There are rule differences in wheelchair basketball that change things a little bit, but you still have to dribble.

“The thing that you start to notice, and that’s what everyone has to learn in practice, is that instead of just a body banging around, you’ll hear a little more metal crashing into each other. That’s when you know someone’s comfortable with it, whereas there are guys that are very apprehensive about smashing into something.

“They’re the rookies!” DeAngelo says with a laugh.

The NWBA, NBA and NCAA are more similar than they are different.

The rules are the same as in the NBA; court dimensions and basket height are the same. There are some rule differences; traveling in wheelchair basketball consists of touching one’s wheels twice after dribbling the ball. There is no double dribble rule, as DeAngelo notes: “That allows you more maneuverability, so you’re not constantly dribbling, or else you really wouldn’t go. Some people can do that really well, but this allows you to maneuver faster and keep the pace going.”

Another difference is that with the nature of wheelchair basketball being such that teams can’t trade players or acquire free agents…players generally play for the team where they live…the best teams become the teams that retain the same players long enough to gel.

“In any team sport,” DeAngelo says, “the longer you keep a nucleus together, the better that team is going to wind up being. We’ve played against teams constantly who’ve grown; a lot of the players were not that good and all of a sudden they start to gel and get better. Year after year you see them grow and they become a powerhouse. North Carolina had always been a good team, and last year was finally their year where they just clicked.”

The NWBA has seven divisions, ranked by the level of competition. The Magee Spokesmen play in Division III, where DeAngelo says most teams are. Division II, he says, is an entirely different animal.

“You have teams out there who are competitive, you have teams with players that are just out there playing, and that’s great. They love to play, they know they’re not that good but they’ll travel to a couple of tournaments and just play. It’s not all about trying to win a championship to them.

“The more competitive you get, yeah, it gets dangerous,” he says.

Yes, DeAngelo has sustained some injuries in his career. In that regard as well, wheelchair basketball is no different from NBA basketball.

“I was playing this past weekend down in Virginia Beach, going for a rebound, another guy’s coming from the other team and wham! We just smashed into each other. I took the brunt of it, I’m not the biggest guy, and I just tumbled to the ground.