The Old Ball Game – SJ Men’s Senior Baseball League

The South Jersey Men’s Senior Baseball League is a haven for men in their advanced years who still can and want to play some baseball. I wrote this piece for the August 2012 issue of JerseyMan; you can view the PDF from the magazine here.

Waiting on the high hard one, adjusting for everything else.

The Old Ball Game

After 20 years, the South Jersey Men’s Senior Baseball League is stronger than ever.

On a picture-perfect Sunday morning at Doc Cramer Field in Manahawkin, the Hammonton Black Sox are playing hooky from church to play baseball, in a time-honored tradition that a Benevolent Supreme Being isn’t likely to mind.

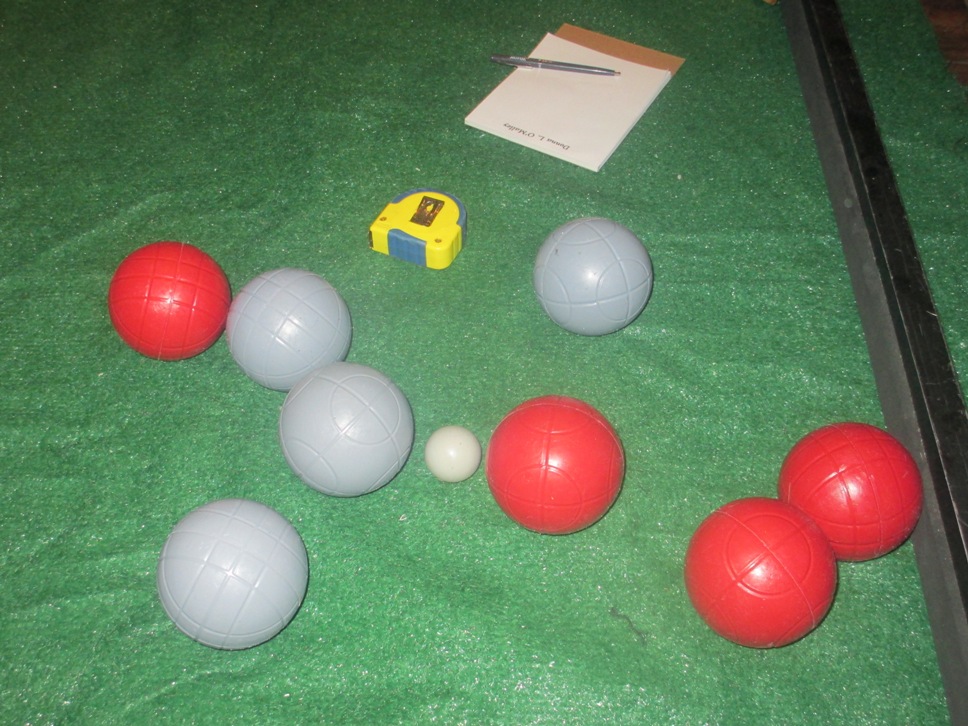

With his team shorthanded, manager Mike Dunleavy must take the field and has enough to keep him busy, so he lets this observer keep score in their game against the Ocean Pirates. At one point a Sox player slaps a weak chop that travels about ten feet but successfully moves the runner on first over to second. There is a dispute over whether it counts as a sacrifice. “You’d be surprised at how much these guys look at their stats,” Dunleavy tells a writer who, as a former softball player, is sure he wouldn’t be surprised at all.

The team has several batters hitting over .400, but they’ve managed little offense in this game. “Junkballers,” the manager says, of his hitters’ performance against the Pirates’ Jeff Martin. “We always have trouble with them.”

In the bottom of the ninth, he calls a conference on the mound with his pitcher Tom King, to figure out how to pitch the Pirates’ Eddie Titley with a runner on second and the game tied. Over King’s objections, Dunleavy orders Titley to be put on intentionally. King, who has pitched a fine game, walks the next two batters, and the Pirates take a 3-2 victory over the Black Sox with two runs in the ninth. Despite its painful obviousness, the manager feels compelled to point it out: “Tough loss.”

Following the game there is a brief shouting match in the dugout between Dunleavy and King over the decision to walk Titley, which is fairly quickly smoothed over. It’s not a contract year, after all.

“From eight to eighty, the game is the same,” Dunleavy says. “It’s still about pitching and defense. There’s nothing I can tell these guys that they don’t already know.”

And so it goes in the senior fast pitch baseball world.

Dunleavy has managed Hammonton’s team in the 45+ American Division for seven years. When his team is shorthanded he will take the field, and occasionally he takes the mound to pitch. At his advanced age, he isn’t stealing bases or hitting bombs or overpowering hitters, but like most pitchers he can still pitch a successful game if he keeps the ball down. The Pirates, he says, are their friendly arch rivals—the Black Sox had lost to them two years before in the championship game, and had beaten them last year for the championship. It’s not Yankees-Red Sox, but it still fires up both teams.

Taking the field in Camden for the All-Star contest.

On July 15 of this year, the South Jersey Men’s Senior Baseball League celebrated its 20th anniversary at Campbell’s Field in Camden. In a brief on-field ceremony, league president Lou Marshall and vice president Neil Hourahan presented league founder Bill Curzie with a plaque, as a thank you for being the indefatigable spark for the SJMSBL and a key ingredient of the glue that has held the league together for 20 years. Whether it is attributable to the league’s success is not certain, but Curzie does not appear to have aged at all in two decades, and at 77 still looks fit enough to play two.

In 1992, at the age of 57, Curzie met up with players of a Pennsylvania division of the MSBL, and asked about setting up a fast pitch baseball league in South Jersey, which had none at the time. National league president Steve Sigler enthusiastically gave Curzie permission, and off he went.

With the help of a story in the Burlington County Times—that began with the words “Curzie is serious”—Curzie spread the word quickly. It turned out that South Jersey was heavily populated with thirty-, forty-, fifty- and even sixty-somethings who still wanted to play ball—and didn’t mind faster pitches or nine innings, the way the game was meant to be played. In less time than it takes a superstar free agent to say “it’s not about the money”, there were enough players for four teams, and the league began with six.

With the help of Curzie’s equally dedicated assistant commissioner Gary Brown, the SJMSBL kept growing, and is now the second largest senior fast pitch league in the nation, with over 1,200 players in four age brackets. There’s been a 25% growth in the 18-year-old group, which bodes well for the long term health of the league. They are adding a 55+ division next season.

Curzie shares the story of his standing firm on the league moving to wooden bats, after the national disgrace of aluminum bats had been the norm for some years in nearly every league. Today, most fast pitch leagues are back to using wooden bats, and Curzie humbly accepts some of the credit for that. When asked the ridiculous question of why wooden bats over aluminum, he has a simple response: “It’s just baseball, man!” He does elaborate further, though. With the reflexes of players at this age, aluminum bats are more dangerous, and besides, there are too many cheap hits with aluminum.

Today Marshall and Hourahan now handle the running of the league. The list of administrative tasks is long. In the beginning of the season, Marshall must be in continuous contact with the national headquarters of the MSBL, ensure that fees are collected, manage schedule changes, work with the umpires’ organization, deal with the inevitable problems that teams will have with the schedule, and arrange the All-Star weekend in Camden.

It’s a lot of work maintaining the league and playing on top of it—a full time job, Marshall admits. It’s all worth it, of course. He echoes the sentiment of the players on the field: “you feel like you’re eight again.”

Bill Curzie accepts an award for putting players back on the field again.

There aren’t hot dogs, exploding scoreboards or the roar of the crowds. You won’t see players at the level of Andrew McCutchen or Mark Teixeira here. But you might appreciate, as these fellows do, how difficult it really is to throw out a baserunner attempting to steal or to turn a double play. Dunleavy says, “Hunter Pence can throw out a guy at third base. We would need a couple of extra throws to get the ball there.”

Perhaps, but that’s an exaggeration that doesn’t give credit to the skills many of these fellows have.

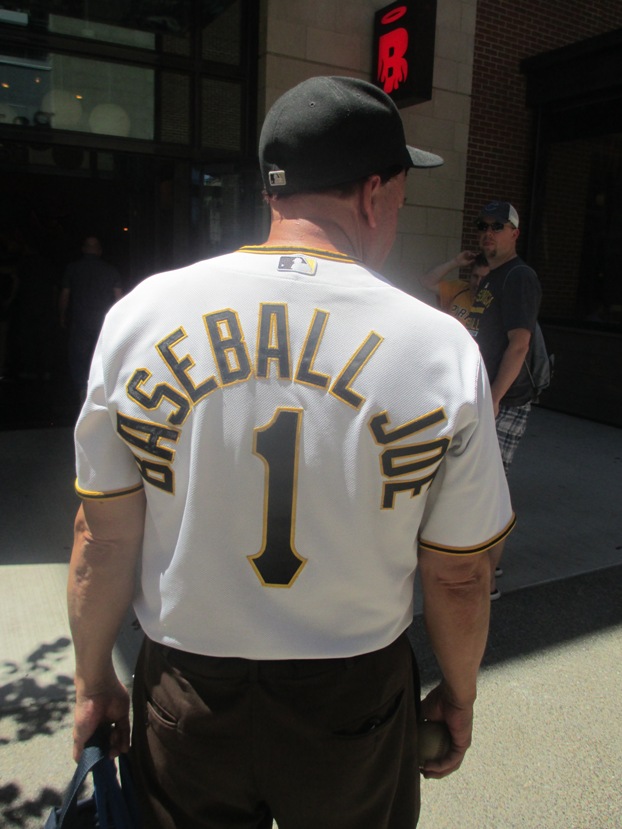

They wear uniforms and cleats. They steal bases. They take advantage of fundamental mistakes. They throw the ball around the horn after a strikeout. They use leg braces and pine tar. Balks and infield flies are called. There are rundowns, pickoffs, and lots of spitting. There is pressure to win, real trophies, and real statistics displayed online that people from here to Cambodia can see.

Some players even look for that little bit of rule-bending edge. Marshall tells the story of a pitcher loading a ball with tobacco juice and snot; eventually he even bought a container of K-Y at the store with his wife present—assuring her it was for his “other slider”.

Being an umpire, which pays in the neighborhood of $80 a game, is just as thankless a job as it is at any level of baseball. Players gripe about calls throughout the game, which the ump, who wants to appear professional just as the players do, mostly takes in stride. Between innings an umpire shares stories about rare times where he’s ejected players. One involved a thrown bat making a loud clang; another involved foul language directed at him. But most times, he says, if he’s got to be out in the heat, then so do they.

Stars of the league.

The SJMSBL is a haven for men refusing to age—who desire to compete on the highest level they can, relive the playing days of their youth, and many times to do both.

Anyone can sign up and play. It’s a time commitment; players give up a day of their week, in this case a Sunday morning. They’ll need legs too; they’re going to be running the full 90 feet between the bases. Some of them will get hurt in battle; many of the Black Sox’s best are currently on the DL. During the interview, Marshall—who still plays while running the league—shows me elbow scabs from sliding.

Never once does it occur to any of them that none of the games will be on television, that they won’t be driving a Porsche with their contract, or that it’s highly unlikely anyone besides an insurance company will ask for their signature. They are playing a boy’s game again, and loving every second of it. Who wouldn’t leave it all on the field?

Dunleavy remarks: “I have seen in the faces of the older guys what men’s senior baseball has done for their spirit. They never thought that they would ever get the chance to actually suit up and play competitively again.”

From eight to eighty, the love of the game is the same too.